For over four decades he is part of graphic art in Argentina and the United States, amongst other countries. He creates images that far from illustrating or complementing a text, editorialize, are ironical, express opinions and are questioning. Until very recently he exhibited a part of his extensive and technically diverse work at the Teatro Argentino. In this interview, he talks about his work, his trajectory and motives of inspiration.

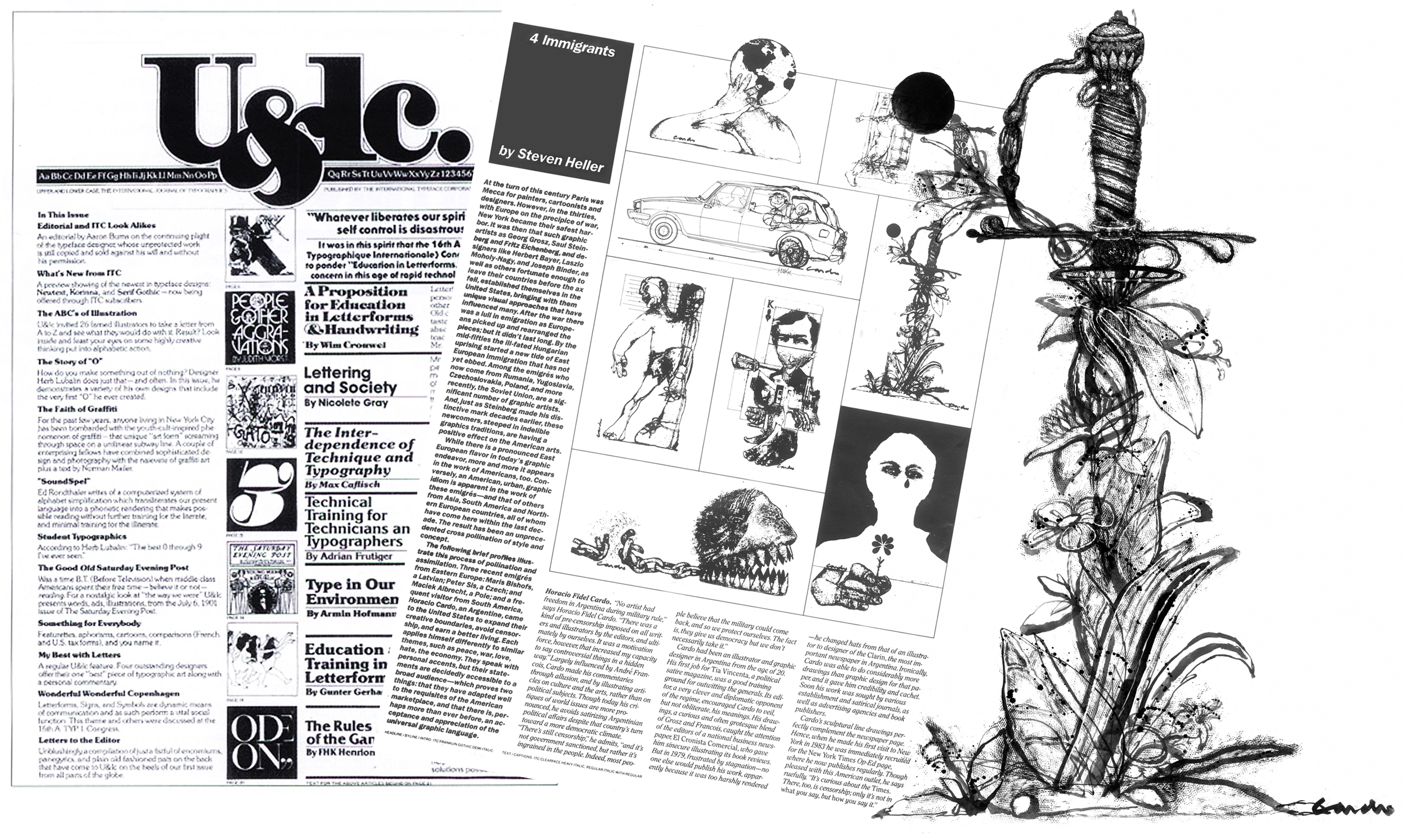

Horacio Cardo was born in 1944 in Temperley, province of Buenos Aires. He currently lives in Pinamar, where he works in his two passions: illustration and painting. Illustrator of Clarín newspaper for twenty six years and in fact, from there, his work has become well known by the public. He lived in Manhattan, New York, where he regularly worked for the New York Times, since 1983 to 2007. His drawings were simultaneously seen in almost every newspaper and magazine in the United States, as much as Europe and Asia. He illustrated posters for movies and Broadway plays, and books for several editorials, amongst which are covers for Planeta Editorial, Madrid.

He received more than twenty national and international awards and was even nominated for the Pulitzer Prize by Jack Rosenthal, Chief Editor of the New York Times.

At the age of twenty one he started working for Fabril Editora Company. What impression do you have from that experience? In what ways did those years contribute to your later development?

It was my first adaptation to graphic demands. Until that moment I had painted and illustrated and drawn freely and I had never worried about how not to cause unnecessary problems to printers and engravers (consider that I am talking about 1965), nor for how to make the best out of the limited possibilities with which you counted then. That can be easily seen if you observe the drawings I made for Jorge Luis Borges and Silvina Bullrich’s book “El Compadrito”, that were gently described as “very personal” by a critic from La Nación newspaper. Under the view of what our job is nowadays, I can’t understand how Chief Editorial Jorge Iaquinandi did not object to them. There was high respect for the illustrator’s work, who were considered co-authors of the intellectual material.

While working for the media, what benefits and creative problems does the delivery time limit cause?

Adapting to the newspapers, where most times, delivery must be done immediately, frantically activates the associations generated while reading the material. The mind works in flashes. It takes on a rhythm that cannot be maintained for long and ends up wearing you down. Then the batteries re-charge again, getting ready for another acceleration. That is the way I feel it. The negative aspect of adapting to a job with such little time for delivery is that you must send everything you have done, whether you like it or not and

the more you look at the drawing, the more changes and improvements (or even an entire and completely different approach to the subject) prove that would have been necessary. Those torments disappear with time and you limit yourself to waiting for next day’s edition buries the sad memory that the previous one may have left.

The rush sometimes becomes a vice and when you have lots of time to conceive the way of executing a painting, ends feeling confused, multiplying unnecessary paths that end up tiring and wearing us down.

While sketching for a drawing that will accompany an article or interview, what is your working method? Do you read it before you start working on an image or do you draw based on a summary or an idea about the subject proposed by the editor?

Most times I read the article or interview. There are some others when it has not arrived yet, but the author has sent a summary in which he informs what he will be writing about. In both cases, the extract is done by the illustrator. A central idea is illustrated, either written or insinuated by a group of factors. Years ago, I used to work for different sections of the New York Times. Amongst them, the Weekend Review, that closed on Saturdays. The Art Director had the habit of literally keeping to the text, in spite of not being notoriously impossible (let me add that in the United States it is habitual to present a previous sketch of the final original, which European tradition —used in Argentina— is and was considered almost offensive). When you presented an idea, the Art Director would fire back with the reading of another particular paragraph, then, if you illustrated in accordance to that paragraph, he would bring forward another one, and so on, considering the mood in which he had got up that day. Because if you read a text, you will see that different concepts are connected in reference to a final intention. Until one day, everything went wrong and I finally told him in the worst way that I never wanted to work with him again. The paradox is that, apart from designing for the Times, he also worked as a free-lance illustrator.

Could it ever happen that you had to make an image to an interview or article that expresses ideas or thoughts with which you disagree? In any case, how do you manage your own opinion about the subject written?

That happens, indeed. In the United States, the Art Directors usually ask if you agree or not and if you wish to illustrate the article that you are being sent. That is very respectful. If you work for someone and you illustrate a particular section regularly, you resort to irony to get rid of the complicity that would mean to reaffirm that is written.

To find a way out to this kind of situations, the editors of the Op-Ed (opposite page of the Editorial) of the New York Times, conceived in 1988 the idea of publishing images that were independent to the text, together with a headline. They were called “Free Statements”, something similar to independent opinions, but the idea did not take on. Years later, during a visit to Paris with Jerelle Kraus —former wife that belonged to the staff of Art Directors of that newspaper— we commented to the Art Director of Le Monde, Dominique Roynette, who was dedicated to re-designing the newspaper and she put it into practice.

Are there moments in which you have to limit the allegoric intention or those in which the relationship is near realization? When this happens, how do you work it out?

The mass media holds in a great scope of people. In order to understand the contents, it is usually recommended to work for the proverbial common cause, which no one can determine. Every time I illustrate something, I ask two or three people what it is that they see in the drawing. I try in a smaller scale, to be as clear as possible, but I think that it is unreal to think that the majority will understand.

Which is your style ? How did you get to it?

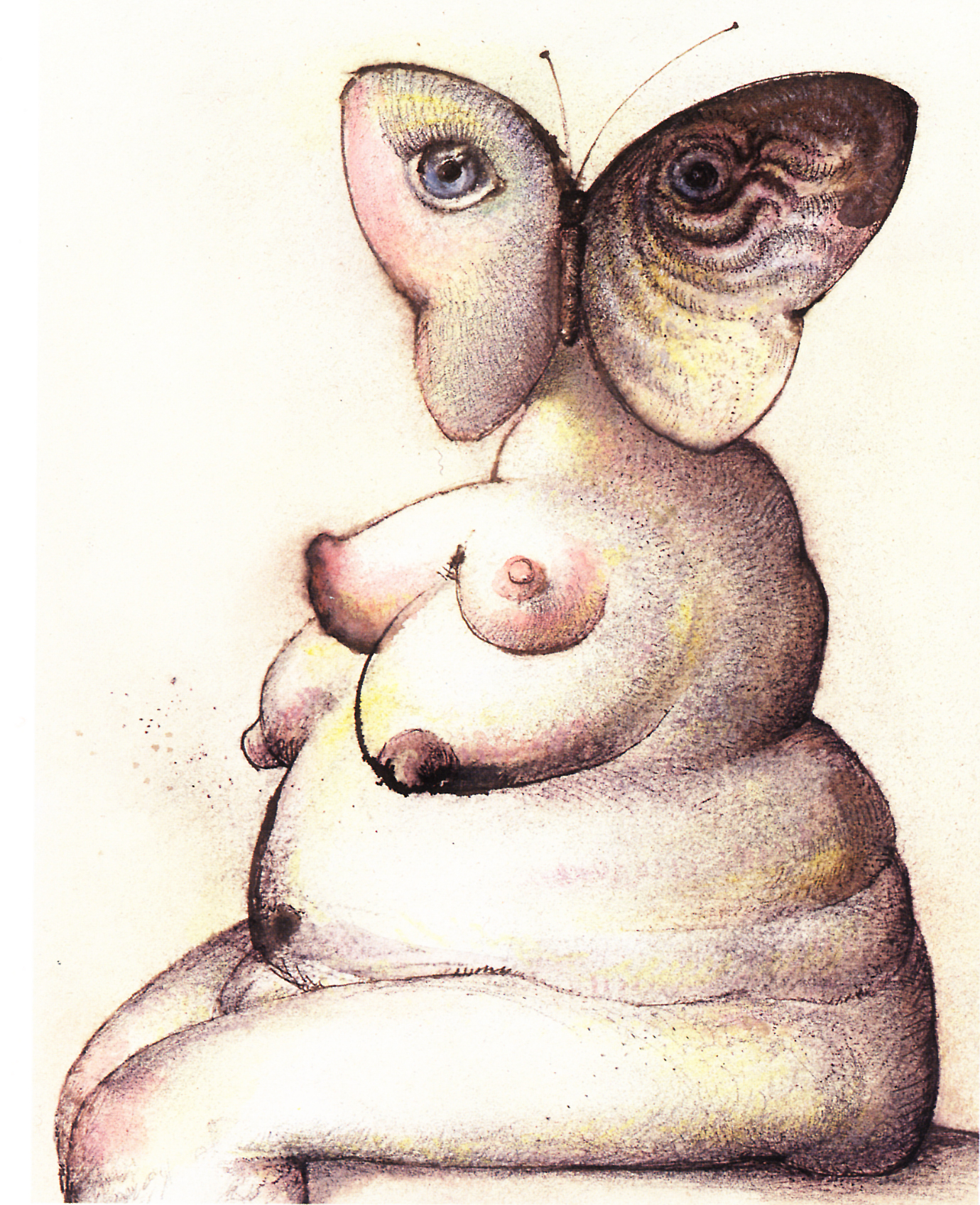

I think it is the outline of my paintbrush and the technique I created to work originally only in black and white in the newspapers decades ago. Despite the dramatic technological advances, I try to preserve that personal touch to plan diverse and various ideas. It is possible that other artists do not coincide with this, to do it otherwise would be equivalent to speak with a different voice just for the fun of change. I think we owe Picasso the haste for change that is given nowadays, in spite of the fact that the Great Masters, who have at some point reached a certain personal maturity, fitted to the means to communicate.

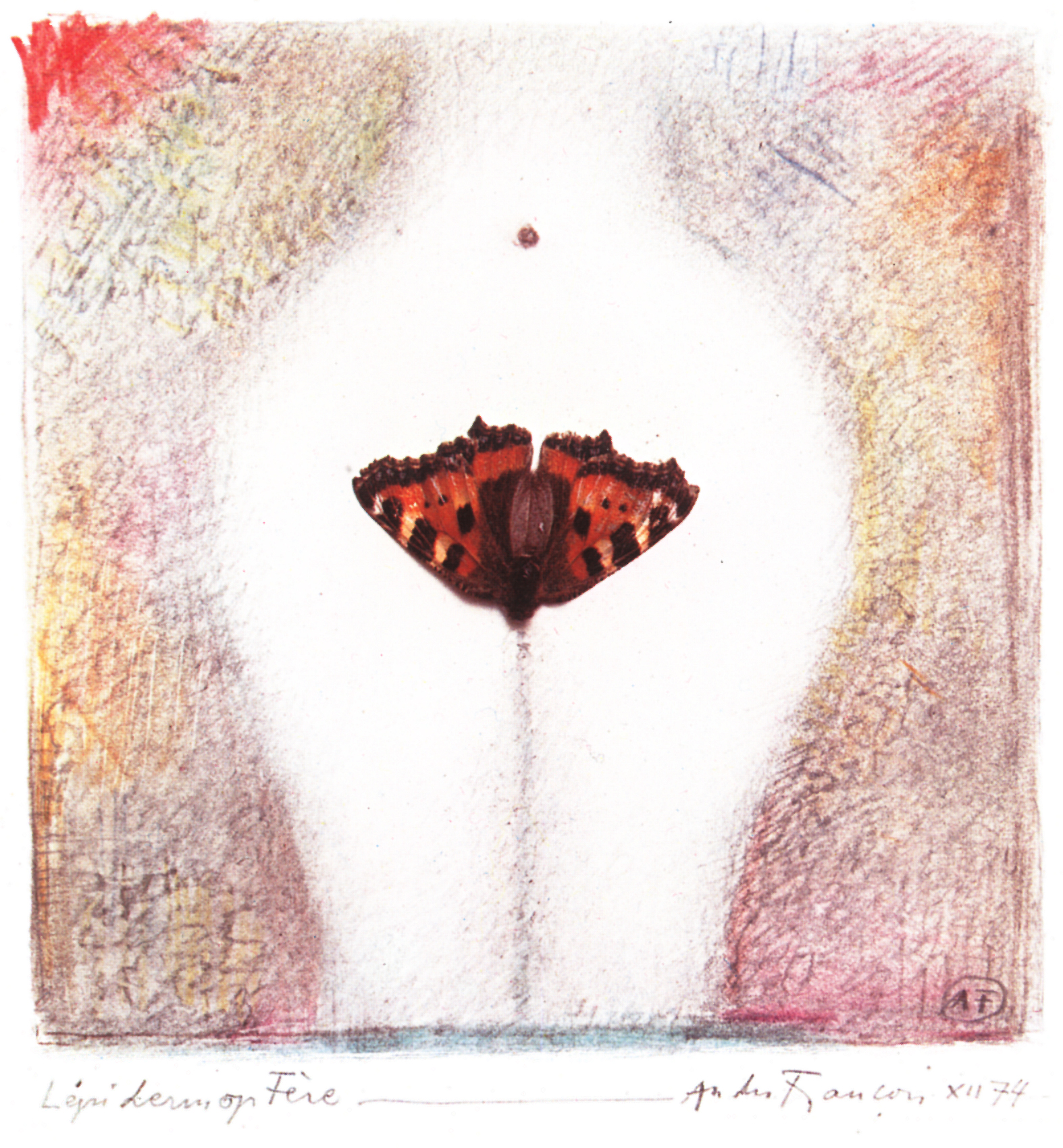

One of your resources is collage. There are great collage teachers in the avant-garde art and the denunciation art performed as from the beginning of the twentieth century up to nowadays. Is this also for you a technique that is associated with certain rebelliousness?

I don’t consider the use of collage as a form of rebelliousness, least of all nowadays, when its use is so widespread. I don’t consider that artists that used it in the past have innovated in that respect, since African art, for example, uses it freely and unreservedly. Collage is a strange object, like from another dimension, that is eaten by the drawing’s antibodies, but end up changed by that action. The enrichment achieved by its use is impossible to fulfill otherwise, and digitalization has notoriously opened its possibilities.

Three of the illustrators whom I had the chance to interview (Hermenegildo Sábat, Oscar Grillo and yourself) name expressionism as the artistic movement that identifies you. What does expressionism have that it enables to preserve its force and validity and why do we feel it so close to our sensitivity?

My opinion is that expressionism is something more than a movement, because it exceeds the pictorial treatment, the search of an original way of working. I think that expressionism resides within every artist, whether he admits it or not. It’s like a dramatic eruption possessed in spite of oneself. That is why, even when it was officially conceived a long time ago, its sprouts will remain intact for as long as art exists.

Amongst your artistic elections are Egyptian and Pre-Columbian art. How do you think the artist and his creation are placed nowadays in relation with these times in which art was not personal but communicative and it was performed with pre-established composition and motifs, and not as the expression of an individual inspiration?

What I treasure from them is exactly their communal character, not the proceedings surrounding the realization. Because I don’t conceive what sense may be in art that does not interact with the community. Our means of communication and Internet are the equivalent of public monuments of the past, and they provide us with optimum conditions to perform community art. What is notorious is that, given these possibilities, the establishment has undervalued it.

What motif, figure or color is your constant?

This is the question, that if I could answer would end with the constancy in my work. I wish I could have the capacity to move with absolute freedom.

Where do you go for a source of inspiration when you don’t have a subject given from the outside?

To myself, but shortly after going down that path, I find it extremely limited, boring and repetitive. I once dreamed I was in a huge plain, surrounded by silent humanoids. A large moon, buttoned to the sky, gave light to all the valley, while an imposing voice read a series of very boring and monochord stories. I asked myself, who could ever be interested in such vulgarities. I was then aware that the voice retold my life: I had died and was listening to all the enumerations freed of my ego. This is what I mean.

Which are the advantages of working with the new technologies? Has anything been lost with regards to when everything was handmade?

The new technologies have provided man with extraordinary tools. Whoever has worked in graphic arts during —lets say— forty years, knows perfectly well what I am talking about. Nowadays, a great deal of work is handicraft. There will always be those who complain or reject advances. Years ago, an artist who visited me, happened to admire a 3 dimension work of mine until she came closer to it and almost shouted: “This is not fair!” When I asked her what she meant, she told me I had cheated: using airbrush. Some ancient artists painted the depth of the sky using up to forty layers of very pale blue oil mixed with layers of insulation. Should an artist nowadays have to use the same procedure? The hyperrealistic painters use the airbrush not to treat an area, but the entire surface of the painting, and it is considered art. The use of the slide projector is also questioned. What is the difference between the use —clearly in disadvantage— of grids used by the ancient artists? And didn’t the Dutch artists use a closed, dark box, with a frontal hole that enabled the pass of light (the scene), which was projected over some posterior sort of paper? (in other words, they traced reality). Nobody refuses or questions them, however. I think we are in the presence of a verbal excess in an almost unnecessary field.

To what subject, character or situation would you dedicate an illustrated book?

I have written and illustrated a presumably sarcastic and imaginary book, based partly in Freud’s life and his absurd delirium of selves, super selves, Electras, Edipos, the wolf man and other colorful characters from masterpieces which he ruined when he immersed them into the pseudo-scientific world, but I dedicated it not in admiration, but by profound disgust, for the enormous social damage that his huge ego had caused. In a few years, nobody will understand how this nonsense lacking all form of scientific basis (now it has been demonstrated that almost all the cases he presented as example had been made up) made such an impact, that it even had a word in the outcome of life and death in many people, as it was considered an important tool to be used in various disciplines, especially by judges.

Javiera Gutiérrez